The ZX Goldenyears web page about the early days of the industry in Liverpool has stopped working. Luckily it is still in the Google cache. I am copying it here so it doesn’t get lost:

Before the 1980s if you wanted to buy a computer off the shelf it would set you back more than £500 (a king’s ransom in those days) and would have probably been imported from the States. Therefore, most budding computer owners built their own, after all, if you held an interest in computers you were probably an electronics nut anyway, used to building radio sets and calculators. Or maybe you’d be an academic or science professional, since the only people lucky enough to use a ‘real’ computer were those who worked in large universities or research institutes. These early machines may not sound attractive, but it would be foolish to believe that there was no market for them.

In the late-Seventies, Bruce Everiss was an accountant with an interest in computers. He had already set up a computerised book-keeping company called Datapool Services in Liverpool, when he began to make plans to open a computer shop in the city. The computer press of the time was limited, to say the least, but stories about new systems from the other side of the Atlantic persuaded Everiss that this was a market on the brink of something special. “So I begged, borrowed and stole so I could rent a shop. We opened in July 1978.”

To begin with Microdigital stocked Apples, NASCOM and S100 machines. Then came the Science of Cambridge SC/MP 2, HP 85 and Commodore PET. Mountains of books were sold too, satisfying enthusiasts’ thirst for knowledge. There was even a repair service for home kit builders and a magazine called Liverpool Software Gazette. It was a place where teenagers were encouraged to come on a Saturday morning to play with new technology, and where budding computer owners could finally buy across the counter rather than by mail order, with its inherent lack of customer service.

It was an exciting time for Everiss; at the tender age of 22 he was presiding over a landmark in British computing and in such a small pond he was able to make a big splash. This was typified by the time that he announced to anyone who would listen that he would not be stocking Acorn’s new Atom computer due to the manufacturers’ production problems. His outspoken behaviour led Personal Computer World to describe him as ‘incorrigible’ and would earn him a reputation within the industry as a man apt to make memorable pronouncements.

It wasn’t just people looking to part with cash who were coming through the door, there was also an army of young enthusiasts who were eager to join the staff and sell these amazing new machines. And it was this group of employees that would come to form the basis of Liverpool’s remarkable computer scene.

Within two years of its opening the company had expanded to a point where Everiss was finding it difficult to manage with so little business experience. One of Microdigital’s customers was Alan Sterling, a director of the hi-fi chain Lasky’s, and he offered a solution. As Everiss explains, “They made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. We set up stores within stores nationally for them and then integrated into their mainstream.”

Many of the Microdigital staff moved on to set up a software company called Bug Byte, while Everiss spread his talents around. He approached publishers Felix Dennis with the idea of a trade magazine; the result was Microscope, which is still running today. He also worked for Bug Byte on a consultancy basis, helping with their marketing, a field in which he always showed great aptitude. He even dabbled in journalism, before moving into his next permanent position.

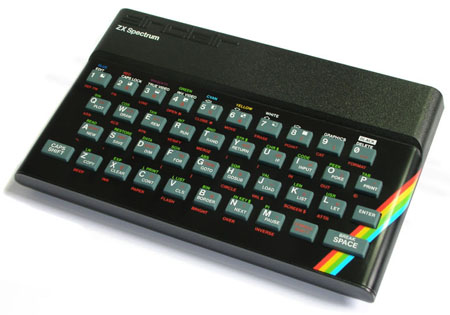

Bug Byte followed the trailblazing efforts of Microdigital by rapidly becoming one of the leading software companies in the country. It had been founded by a handful of the few computer ‘veterans’ in the country and they put their experience to good use in producing some of the most memorable early titles for the ZX81 and the ZX Spectrum. Their success attracted talented programmers like Matthew Smith, the genius behind Manic Miner, and for a while their continued success seemed guaranteed. However, with so much creative talent trying to express itself, it was inevitable that some members of the Bug Byte team would want to move in their own direction. Most memorably, Alan Maton and Matthew Smith split off to form Software Projects, while Dave Lawson and Mark Butler left to create Imagine Software.

In 1982 Bruce Everiss was invited by Lawson and Butler to become the operations manager of Imagine. Success had come suddenly for the new company thanks to Arcadia, a shoot ’em up title written by Dave Lawson. For a brief, dynamic period Imagine came to represent the meteoric rise of the home computer industry; a shining example of the sort of affluent lifestyle that could be achieved in this almost mythical new medium. Not that the directors of Imagine were only interested in success – they wanted to be seento be successful too. This required media attention and now the Bruce Everiss PR machine went into overdrive, ensuring that Imagine achieved the sort of exposure that other companies could only dream of.

Looking at the back-catalogue of Imagine games it’s difficult to understand how they prospered to the extent that they did. So much of it had to be due to the level of hype they generated, fed to a software-hungry market with few preconceptions. And head of hype was Bruce Everiss. Perhaps his greatest feat was to attract the attention of the general media with a wild story of how 16-year-old programmer Eugene Evans (another ex-Microdigital employee) was on a salary of £35,000 per year and owned a sports car that he was too young to even drive. “We had to bring computer games to a wider audience,” says Everiss on the subject, “and the cult of personality was a tool we used.”

The Imagine HQ reeked of success. It was a plushly-carpeted office, decked out with dozens of expensive Sage terminals, staffed by nearly a hundred programmers, technicians, artists and musicians. Such extravagance seems to have been justified at the time, after all, they were doubling their turnover every month. “We knew that we were going places,” explains Everiss. “Some at the time called it arrogance and maybe they were right. On the inside it was just hard graft and constant success.”

However, the bubble was about to burst. Much has been made of the effect of the ‘Mega Games’ and they have often been blamed for Imagine’s downfall, but there were many other factors to take into account. The Mega Games were intended to be a revolutionary way of taking Spectrum Software a step further. They would use a hardware device that would be attached to the back of the computer, granting extra memory and eliminating piracy in one blow. The only drawback was that the games never got further than the design stage, while the intended cost of £30 would have been unworkable in an increasingly competitive market.

They were not the cause of Imagine’s downfall though. Far more important was complacency and a delusional belief by directors Dave Lawson and Mark Butler in the the sort of hyped corporate self-image that Bruce Everiss had created. It was an expensive image to maintain and several of the director’s decisions made it increasingly difficult for Everiss to sustain Imagine’s success.

During the Christmas of 1983 Imagine had bought out the entire capacity of the country’s largest tape duplicating plant in an effort to scupper the output of their competitors. This apparent masterstroke backfired horribly however, leaving Imagine with a warehouse full of unsellable stock, forcing them to slash their prices in the New Year and infuriate retailers in the process. Their second misjudgement was to agree to write software for the publishing house Marshall Cavendish. The sort of games that were expected and what Imagine were able to deliver in the time available differed somewhat, and when Marshall Cavendish pulled their investment it tighten the screw on a company who were spending a vast amounts of money to keep themselves at the top of the software tree.

“There were two main problems with Imagine,” comments Everiss. “Firstly, the cost base became too high, too many staff and very expensive office accommodation. Secondly, development stopped producing product to sell, they expected the existing catalogue to sell for ever.” With unpaid creditors blocking the phonelines, the end was nigh for Imagine. As the crisis intensified, Dave Lawson, Mark Butler and financial director, Ian Hetherington, became distant figures, scarcely seen about the Imagine offices. When the bosses did meet, discussions about the Mega Games went on as though their problems didn’t exist. “I think it was very difficult for anyone to accept reality,” said Everiss. “For a star to shine so bright and fall so fast. It was impossible to take corrective action as the whole mentality and decision making process was founded on continuous success.”

As the foundation of success on which Imagine was based began to disintegrate, Hetherington began laying plans for a ‘lifeboat’ – a way for Lawson, Butler and himself to jump ship unscathed. In the meantime Everiss was fighting to pilot a rudderless ship. It was only towards the end that he became aware of the extent of the problem. “I’m not a signatory on the bank or anything,” he said at the time, “but I’ve had a look at the financial records of the company and there has never been a VAT return, never a bank reconciliation, never a creditor’s ledger control account, never any budgeting, never any cash-flow forecasting, no cost centres, not even an invoice authorisation procedure. Just no financial controls at all.”

Remarkably, the death of Imagine was recorded by a BBC film crew as they were making a documentary supposedly based on the success of the British software industry. What they ended up with was something very different. In the final weeks, the Imagine offices began to descend into chaos, with Everiss attempting to hold what remained of the company together. Employees were sitting around playing games and watching videos, while others entertained themselves with fire extinguisher fights. Lawson and Hetherington had vanished to the States, leaving Everiss to try to find jobs for around 60 people. Beleaguered and defeated, he was left with no option but to resign. “Dave and Ian, being too much of cowards to face up to me, have told Mark that they wouldn’t want me here when they returned,” he remarked at the time.

In the immediate aftermath, Everiss admits that there was considerable acrimony, but in hindsight he has only one real regret. “That I stayed at Imagine too long. Once the writing was on the wall I should have taken my then intact reputation elsewhere. Loyalty did not serve me well.”

In 1985, Bruce Everiss joined Tansoft, the owners of Oric as managing director and made a typically bullish announcement: “My first aim is to establish the Oric Atmos in its rightful market position.” On hearing this his predecessor, Paul Kaufman, said, “His reputation says it all. The only thing that annoys me about his appointment to managing director is that he is now driving around in what used to be my Mercedes.”

Sadly, Oric was fighting to survive in market completely dominated by the Spectrum and the Commodore. Although it had a foothold in France, in the key market of the UK, it failed to impress. In a trade journal, Everiss said, “Oric’s performance in the UK this year was a total disaster. The company built up massive debts and is scheduled to repay £3.5 million to creditors by March.” Everiss was about to find himself aboard another sinking ship.

In 1986, after Oric had folded, Everiss joined the newly formed budget house, Codemasters in 1986 for a year, looking after their marketing. For him it was like being involved at the start of Imagine again – the excitement and sense of possibility of a new venture. Thankfully, Codemasters was rather better managed than his old employers and in 2000 he returned to them as Head of Communications, taking care of their PR in all the world’s markets. In the interim, Everiss had kept himself busy setting up the All Formats Computer Fairs, which he still runs today and have proved extremely popular in North West England.

Although he has often been considered controversial thanks to his forthright approach, the effect of Bruce Everiss on British computing has been considerable. From creating a cradle of talent in Liverpool, to his involvement in the city’s computing dominance of the early Eighties, he has shown a commitment to the medium that has helped to establish Britain as one of the world’s most important software producers. Furthermore, he raised the profile of computing beyond the attention of enthusiasts and into the psyche of a much wider audience. And for that we should be grateful.

Permalink

Bruce,

I have a question, did you write this article? If so, then why did you chose to write it in the 3rd person? I sometimes write stuff, and whenever I try and do it in the 3rd person about myself it seems ‘wrong’ somehow.

John

Permalink

No I didn’t write it.

As explained at the top it is from ZX Goldenyears.

Permalink

Brave of you to post this, Bruce – it seems to largely blame your hype for Imagine’s collapse! I’d have WANTED that page to disappear off the net!

Permalink

I love stories of the early days. They are often unbelievable and unbalievably dramatic. Quick rises to the top, massive plummets to the bottom, it’s gripping stuff!

Cliffski has a point. I can’t quite decide if the article paints you in a good or bad light. 🙂

Permalink

I think it posts Bruce in a pretty good light – he was the creator of the hype, not the one that bought it himself and started ‘living the dream’.

Permalink

Hi. I saw an old Video Genie photo with “Microdigital” logo printed. Was your brand?

http://classic-computers.org.nz/system-80/other_guises_microdigital%20video%20genie.jpg

Permalink

@Victor

Yes.

A bit more here: http://classic-computers.org.nz/system-80/other_guises_video_genie.htm

Permalink

Here in Brazil there was a Microdigital, a company that basically copied some Sinclair machines in 80’s. I believe that their logo was also cloned from yours.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microdigital_Eletronica